Torticollis / Wry Neck / Sternomastoid tumour of infancy with thanks to Dr Katie Knight

(From Latin tortus = twisted + collum = neck)

Torticollis can be congenital or acquired, but this article will focus mostly on the congenital form, affecting 0.3% of infants and usually presenting in the first 6 months of life [1]. It is the third most common reason for referral to orthopaedics in this age group. The overwhelming majority of cases seen are due to a benign muscular problem, but some more sinister diagnoses can also present in a similar way, so it is crucial to be aware of these.

What causes torticollis?

Muscular damage:

Most cases of congenital torticollis are the result of damage to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) at birth (for example in instrumental delivery) or in the uterus (restricted movement or abnormal positioning causing muscle damage).

Damage to the SCM causes it to shorten or contract as fibrosis affects the area. Fibrotic change in the damaged muscle is felt as a hard lump – the ‘pseudotumour’ of torticollis, as it is sometimes called.

This shortening of the muscle in turn makes it difficult for the infant to turn their head, resulting in neck stiffness and a fixed head position, with very limited neck movement.

Risk of muscular torticollis is increased in intrauterine constraint (eg breech presentation or oligohydramnios [2]), and it is also associated with other minor positional deformities. 10% of babies with torticollis have hip dysplasia. [3] One study looking at 1001 babies found that 10% had one or more postural deformities (in decreasing order of frequency: plagiocephaly or torticollis; congenital scoliosis or pelvic obliquity; adduction contracture of a hip and/or malpositions of the knees or feet [4]. This study found that all these deformities were more likely to be observed in:

- babies with a greater birth length

- breech presentation

- oligohydramnios

- babies delivered instrumentally

- Male infants were also found to be 1.9 x more likely to have positional deformities including torticollis.

With these presenting symptoms described above and nothing else of note, torticollis is clearly the first diagnosis that springs to mind. HOWEVER – to play the devil’s advocate – a baby who presents with ‘a lump in the neck’ and ‘abnormal neurology’ certainly demands a careful history and examination.

Uncommon causes of torticollis

Congenital vertebral abnormalities:

The SCM is supplied by the accessory nerve (CN XI), which exits the skull through the jugular foramen. Anything affecting the structure of the upper cervical spine or skull base could compress the nerve root of CN XI and cause torticollis.

Congenital vertebral abnormalities often come along with other congenital abnormalities, as part of a syndrome (two examples are briefly described below, for interest). For this reason a child presenting with torticollis who is known to have other congenital abnormalities should be carefully examined with the possibility of an unusual syndrome kept in mind. [5]

MURCS syndrome (Müllerian duct/renal aplasia/cervicothoracic somite dysplasia) is a rare condition affecting 1 in 5000 female infants that has been associated with congenital torticollis in some cases due to aplasia of the posterior vertebral arch [6]

Klippel-Feil syndrome – cervical spine fusion is seen along with a host of other symptoms [7]

Posterior fossa tumours, tumours of the cervical spine, atlas and axis – these are very rare and should be part of the differential in older children who present with acquired torticollis. [8, 9] Posterior fossa tumours, when they present with torticollis, usually have accompanying symptoms of intracranial pathology (headache, nausea, vomiting, eye signs) [10]

‘Mimics’ of torticollis

‘Ocular torticollis’ occurs when there is 4th cranial nerve palsy. The superior oblique muscle, supplied by CN IV, causes the eye to look inwards and downwards. Paralysis of the muscle means the eye cannot adduct or internally rotate, and this causes torsional diplopia, which the child ‘corrects’ by tilting the head position. Adopting this position over a long period of time eventually causes contracture of the SCM. [11] This condition can be ruled out by using the cover test (watch a 7 minute long Youtube video with a rather disconcerting picture of a huge eye in the background here). When the affected eye is covered, the child should spontaneously correct their head position (in the early stages, before muscle contracture has occurred).

Examination

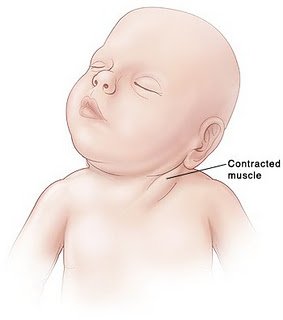

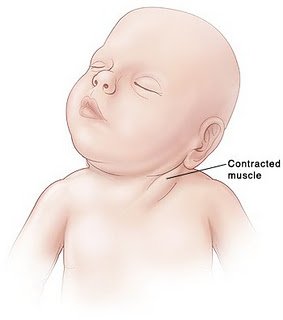

Appearance (see image): The head is tilted to one side (to the side of the affected muscle), and the chin is turned to the other side. There is stiffness, from the lack of movement, so there may be pain when the neck position is passively corrected.

A lump may be felt in the distal SCM.

Lump felt in distal SCM Lump felt in distal SCM

|

Investigation

The key is to differentiate between muscular torticollis (ie common, benign, easily correctible) and non-muscular torticollis (ie possibly secondary to neurological, ocular or vertebral pathology, and needing further investigation.

If there is a lump palpable in the SCM, it needs to be differentiated from other causes of a lump in the neck. Ultrasound is the best first line investigation – it detects fibrosis of the muscle (diagnosing torticollis) but would also pick up abnormal lymph nodes or masses.

Fine needle aspiration would be the next step if there was any uncertainty of the diagnosis, but this is rarely needed.

Treatment

Once muscular torticollis is confirmed:

Physiotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. Even when there is severe fibrosis of the SCM, physio is effective in 98% [12]

- Neck stretches, performed regularly, moving the neck in the opposite direction to the affected muscle (tilt head sideways towards non-affected side, rotate towards affected side). Physio referral is indicated so parents can be taught the correct way to perform the stretches.

- Let the baby spend more time lying on its tummy, to strengthen neck muscles

- Use baby chair or Fraser chair to minimise the time the baby spends lying flat

- Encourage head turning to affected side by using toys, distraction, feeding from that side

- Physiotherapist may advise use of a neck brace in certain cases.

(The above advice adapted from ‘Physio Questions’ [13], a blog by an Australian physio – torticollis featured as a blog entry in August 2010)

Surgical treatment is very rarely needed – only in instances where conservative management has failed after 6 months of treatment. When surgery is performed, the operation is a bipolar release of the SCM, and this has been found to be highly successful, even in patients older than 5 years [14] and into adulthood [15]

Alternatives to surgery?

A recent successful non-surgical development in treating cases resistant to physio is using botox injection. [16] The evidence for chiropractic treatment is weak, isolated successful cases have been described, [17] but there has been no randomised controlled trial. There are also reports of infants with torticollis caused by neurogenic tumours being treated (unsuccessfully) by a chiropractor before the correct diagnosis was made, [18] so it is imperative that parents have consulted a doctor before they choose to seek chiropractic help.

References:

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3566514?tool=bestpractice.bmj.com

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21376202

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7484683

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18795328

- http://web.jbjs.org.uk/cgi/reprint/71-B/3/404

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21553338

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1264848-overview

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22095422

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20638308

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8784707

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/868283

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21843719

- http://physioquestions.blogspot.com/2010/08/are-you-worried-about-your-childs.html

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22045346

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19036153

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16470158

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8263436

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2484567/?tool=pmcentrez