With thanks to Dr Ed Dallas, paediatric registrar, for putting together a succinct guide to eating disorders and the management of re-feeding syndrome.

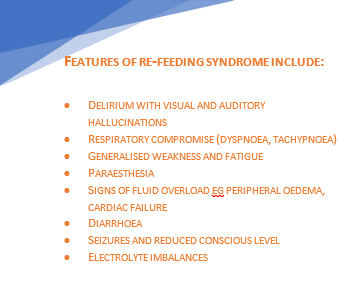

Re-introduction of nutrition to severely malnourished individuals can precipitate refeeding syndrome which may result in cardiac failure and death.

The key biochemical abnormality is hypophosphataemia, due to total body phosphate depletion and a shift of extracellular to intracellular phosphate when the body changes from a catabolic state to anabolic.

The risk is greatest in the initial stages of refeeding (first week). The incidence increases with decreasing BMI and if weight loss is rapid.

Anorexia is a serious, potentially fatal disease—while refeeding syndrome can be fatal, the risk from malnutrition and ‘underfeeding’ is much greater.

In A&E:

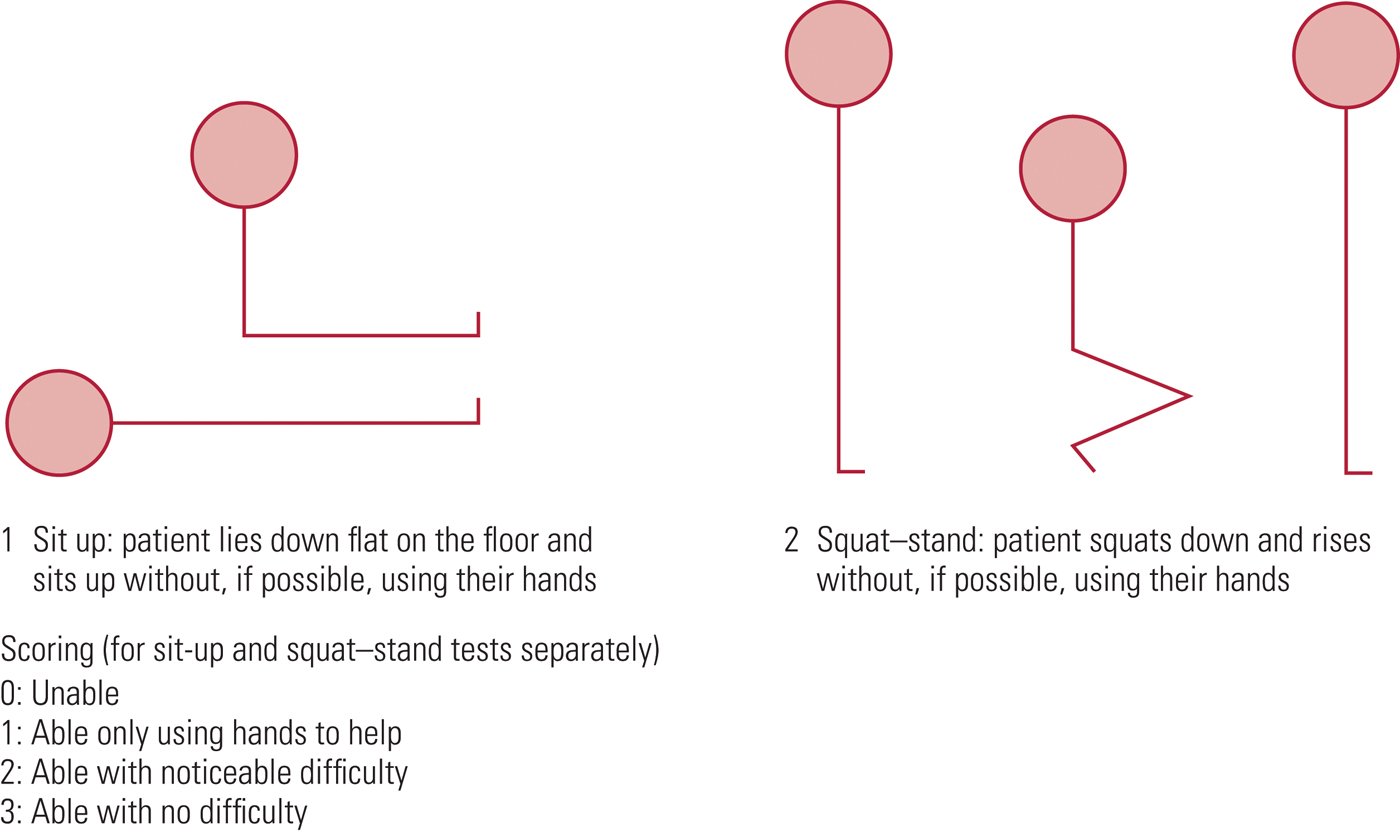

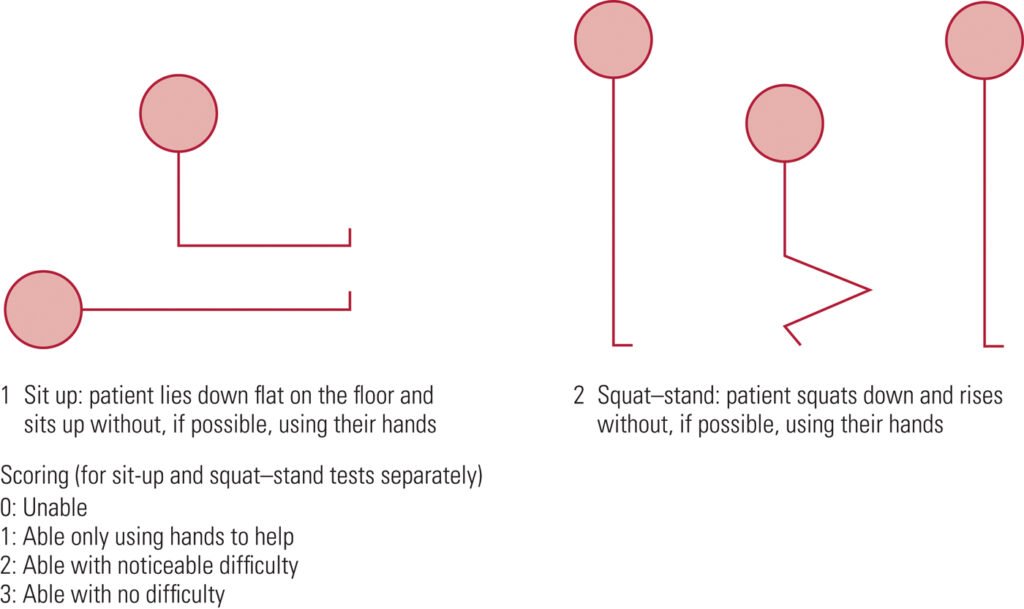

– Assess using SCOFF questionnaire and Sit-up/Squat test.

– Consider differentials for weight loss in children (e.g. Malignancy, hormonal, illness)

– Risk Assessment according to Junior MARSIPAN guidelines: Clinical parameters, location of care, compulsory admission/treatment, legislation (e.g. Gillick competence, Mental Health Act)

See Summary below of what to look for and when to be concerned!

Once admitted:

- Baseline bloods: Red flags: Na+ < 130mmol/L, K+ < 3mmol/L, Phosph < 0.5mmol/L often symptomatic if phosphate <1mmol/L (range 1.3-2.1mmol/L), Glucose

- ECG (look specifically for prolonged QTc)

- For children, use the percentage of 50th centile BMI, not just the BMI.*

- All vital signs, however, are to be checked against standard charts for their age. Patients can be hypotensive, bradycardic, hypothermic.

*Plot BMI on growth chart. To calculate percentage median BMI:

Percentage BMI = actual BMI (weight/height2) x 100

median BMI (50th percentile) for age & gender

Treatment & Re-feeding:

Patient should be fed in as normal a fashion as possible. If this fails, NG feeds should be considered early in the admission. Make the decision within 24 hours. Specialist paediatric dietician must be involved early.

Risk from Re-feeding Syndrome can be reduced by careful monitoring and paediatric dietician input into choice of feed composition. A diet too high in carbohydrates increases the risk of re-feeding syndrome.

Consider phosphate (and other) supplementation early. Replace and titrate according to bloods which should be taken just before the supplement is given. Stores are usually replenished after 1 week but continue for at least 2 weeks. Consider long term lower dose supplementation.

Re-feeding Bloods (U&Es, LFTs, Phosphate, Calcium, Magnesium) to be taken before re-feeding, 6 hours after starting and then daily for 2-5 days, then at 7-10 days, at least until 2 weeks. Ideally, bloods to be taken just before any supplementation are given (so levels are not falsely high).

Patients should not be ‘underfed’ for fear of refeeding syndrome: consider starting at 20 kcal/kg/day, 5-10kcal/kg/day if high risk

CAMHS

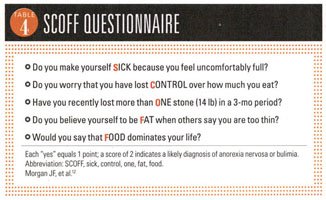

SCOFF questionnaire for screening Anorexia and Bulimia

Shown to have 100% sensitivity and a specificity of 89% for patients with anorexia and bulimia.

*One point for every “yes”

A score of ≥2 indicates a likely case of anorexia nervosa or bulimia

Young people with an eating disorder may deny all the above, in which case it is very important to use your clinical judgement, monitor the situation and provide follow-up.

Those who are High risk for re-feeding syndrome

- Very low percentage median body mass index

- Minimal or no nutritional intake for the past 3–4 days

- Weight loss >15% in the past 3 months

- Abnormal electrolytes prior to starting re-feeding

→ May need a more cautious approach (5–10 kcal/ kg/day starting regimen) with twice daily bloods

Refeeding Plan:

- Paediatric dietician for specialist advice.

- Correct dehydration – usually over 48 hours as too rapid correction can result in cardiac decompensation

- Prescribe multivitamin and mineral supplements; consider thiamine in older children. Start any multivitamins and mineral supplementations before feeding begins (NICE CG9)

- Refeeding should ideally mimic normal eating

- If the patient cannot comply with a meal plan then NG considered by 24 hours. Use a daytime bolus regimen to mimic physiological eating

- Consider starting at 20 kcal/kg/day. Aim for 0.5–1 kg/week weight gain.

- To prevent underfeeding—aim to increase by 200 kcal/day until full nutritional requirements for weight gain are achieved (this should be within 5–7 days).

- If hypophosphataemia develops, maintain rather than reduce calorie intake; consider supplementation.

- Daily Re-feeding bloods (U&Es, LFTs, phosphate, magnesium) during the ‘at-risk’ period of days 2–5 initially, and at 7– 10 days (to identify late refeeding syndrome) up to at least 2 weeks

- Restrict carbohydrate intake and increase dietary phosphate (eg, using milk). If NG feeding, avoid high calorie concentration feeds (high carbohydrate content increases the risk of re-feeding syndrome).

WHAT SHOULD I START DOING?

- Assess nutritional status based on percentage median BMI, and not BMI alone.

- Baseline clinical assessment of risk includes baseline ECG and SUSS test for weakness.

- Have a low threshold for starting NG feeding and avoid an overcautious approach to re-feeding (consider starting at 20 kcal/kg/day and increasing by 200 kcal/day until nutrition is sufficient for weight gain).

- Always consider re-feeding syndrome—monitor patient’s electrolytes (especially phosphate) before and during re-feeding, and assess the risk of re-feeding syndrome prior to starting feeding.

- Prescribe a general vitamin and mineral supplement in younger children, and consider thiamine supplements in older children (main evidence in adults).

WHAT SHOULD I STOP DOING?

- Taking an overcautious approach to re-feeding (may result in underfeeding syndrome)—patients should be receiving sufficient nutrition for weight gain within 5–7 days of re-feeding.

- For patients receiving supplemental or NG feeds, avoid calorie dense feeds, which may be too high in carbohydrates and increase the risk of re-feeding syndrome.

Useful Summary of Marsipan guidelines from BMJ:

https://ep.bmj.com/content/edpract/early/2015/09/25/archdischild-2015-308679.full.pdf?keytype=ref&ijkey=zgb4e3x2vGIWEmL

Link to FULL Junior Marsipan Guidance from RCPSYCH (75 page PDF):

https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr168.pdf?sfvrsn=e38d0c3b_2

Medical Management of Anorexia Nervosa:

Managing Anorexia; BMJ Review:

https://adc.bmj.com/content/96/10/977

Hypophospataemia in Anorexia Nervosa; BMJ review:

https://pmj.bmj.com/content/77/907/305.full