Take a look at September 2012’s edition of Paediatric Pearls! Safeguarding issues surrounding head and spinal injuries, simple motor tics, chronic fatigue syndrome, the new CATS website and some pointers to gems you might have missed from the last 3 years. Do leave comments.

Tag Archives: neurology

child abuse and head injuries

This summarises the Core-info leaflet on head and spinal injuries in children. Full details are available at www.core-info.cardiff.ac.uk.

**PLEASE REFER ALL SUSPECTED INFLICTED HEAD AND SPINAL INJURIES TO PAEDIATRICS **

Inflicted head injuries

- can arise from shaking and/or impact

- occurs most commonly in the under 2’s

- are the leading cause of death among children who have been abused

- survivors may have significant long term disabilities

- must be treated promptly to minimise long term consequences

- victims often have been subject to previous physical abuse

Signs of inflicted head injury

- may be obvious eg. loss of consciousness, fitting, paralysis, irritability

- can be more subtle eg. poor feeding, excessive crying, increasing OFC

- particular features include retinal haemorrhages, rib fractures, bruising to the head and/or neck and apnoeas

- also look for other injuries including bites, fractures, oral injuries

If inflicted head injury is suspected

- a CT head, skull X-ray and/or MRI brain should be performed

- neuro-imaging findings include subdural haemorrhages +/- subarachnoid haemorrhages (extradural haemorrhages are

more common in non-inflicted injuries) - needs thorough examination including ophthalmology and skeletal survey

- co-existing spinal injuries should be considered

- any child with an unexplained brain injury need a full investigation eg. for metabolic and haematological conditions, before a diagnosis of abuse can be made

The following diagram comes from http://www.primary-surgery.org:

These CT images are from http://www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v5c07.html:

EXTRADURAL (or epidural) haematoma

SUBDURAL haemorrhages in a 4 month old

SUBARACHNOID haemorrhage in a 14 month old

Neuro-imaging for inflicted brain injury should be performed in

- any infant with abusive injuries

- any child with abusive injuries and signs and symptoms of brain injury

Inflicted spinal injuries

- come in 2 categories : neck injuries, and chest or lower back injuries

- neck injuries are most common under 4 months

- neck injuries are often associated with brain injury and/or retinal haemorrhages

- chest or lower back injuries are most common in older toddlers over 9 months

- if a spinal fracture is seen on X-ray or a spinal cord injury is suspected, an MRI should be performed

Stages of normal speech development

With thanks to Fionnuala O’Driscoll, Speech and Language Therapist at Wood Street Specialist Children’s Services for the table below:

| Age (years) | 0-1 | 1-2 | 2-3 | 3-4 | 4-5 | 5-6 | 6-7 |

| Attention and Listening | Distractible | Single channelled | Single channelled but flexible | Shared attention | Shared and integrated attention | Able to focus for longer periods of time | Can spend hours on chosen activity |

| Play and Social Interaction | Exploratory, relational or constructive.Eye contact and turn taking from birth. | Symbolic or pretend play.Turn taking in play from 18 months. | Pretend and imaginary play.Plays with others in small groups. | Role play.Cooperative play develops.May like simple jokes. | Chooses own friends.Learn to turn take in conversation.Can discuss emotions. | Able to play games by rules.Plans sequences of pretend events in play. | Group play with less pretend play.Can play alone happily. |

| Understanding of Language | Understands a few simple words (bye bye) | Understands familiar words and phrases in context | Follows simple instructions and later short stories | Follows short stories and longer instructions | Understands stories, longer instructions and conversations | Understands 13,000 words.Beginning to reason and understand abstract concepts | Understanding of vocabulary doubles in size.Understands abstract concepts. Can reason, predict, and infer. |

| Use of Language | Cooing, babble, simple words | First words and later 2 word phrases | 2-3 word phrases – longer phrases | Longer 4-5 word sentences usually well formed (4 yr) | Well formed sentences combining up to 8 words.Tells simple sequence of events. | Longer sentences with mostly appropriate grammar.Tells simple stories. | Uses language for a range of purposes e.g. persuade, question, negotiate, discuss.Tells more complex stories. |

| Speech | p, b, m, w and vowels | n, t, dSpoken words not always recognizable. | k, g, ng, h | f, s, l, y | sh, z, v, ch, th, r, clusters May have difficulty with multisyllabic words (hospital) | Generalising speech sounds to connected speech | Generally mature by 7 years old |

Paediatric Pearls for February 2012

Click here for this month’s PDF digest! It ‘s quite hard providing a balance of information for GPs and ED juniors now that I am only doing the one newsletter. I think we’ve succeeded this month with neurodevelopmental milestones in Down’s syndrome and essential tremor aimed mainly at GPs and pulled elbow, anaphylaxis and the FEAST study aimed more towards the emergency medicine practitioners. Many thanks to my colleagues who have contributed this month. The FEAST video makes fascinating and inspiring watching for any health professional, regardless of specialty. Do leave comments, questions, suggestions!

December 2011. Happy Christmas!

December 2011 has snippets of information on torticollis (backed up with lots more information on the website), unconscious children, alkaline phosphatase and a link to the Map of Medicine’s recent algorithm for cough in children. Also some pointers for your safeguarding training needs. Download it here.

Torticollis

Torticollis / Wry Neck / Sternomastoid tumour of infancy with thanks to Dr Katie Knight

(From Latin tortus = twisted + collum = neck)

Torticollis can be congenital or acquired, but this article will focus mostly on the congenital form, affecting 0.3% of infants and usually presenting in the first 6 months of life [1]. It is the third most common reason for referral to orthopaedics in this age group. The overwhelming majority of cases seen are due to a benign muscular problem, but some more sinister diagnoses can also present in a similar way, so it is crucial to be aware of these.

What causes torticollis?

Muscular damage:

Most cases of congenital torticollis are the result of damage to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) at birth (for example in instrumental delivery) or in the uterus (restricted movement or abnormal positioning causing muscle damage).

Damage to the SCM causes it to shorten or contract as fibrosis affects the area. Fibrotic change in the damaged muscle is felt as a hard lump – the ‘pseudotumour’ of torticollis, as it is sometimes called.

This shortening of the muscle in turn makes it difficult for the infant to turn their head, resulting in neck stiffness and a fixed head position, with very limited neck movement.

Risk of muscular torticollis is increased in intrauterine constraint (eg breech presentation or oligohydramnios [2]), and it is also associated with other minor positional deformities. 10% of babies with torticollis have hip dysplasia. [3] One study looking at 1001 babies found that 10% had one or more postural deformities (in decreasing order of frequency: plagiocephaly or torticollis; congenital scoliosis or pelvic obliquity; adduction contracture of a hip and/or malpositions of the knees or feet [4]. This study found that all these deformities were more likely to be observed in:

- babies with a greater birth length

- breech presentation

- oligohydramnios

- babies delivered instrumentally

- Male infants were also found to be 1.9 x more likely to have positional deformities including torticollis.

With these presenting symptoms described above and nothing else of note, torticollis is clearly the first diagnosis that springs to mind. HOWEVER – to play the devil’s advocate – a baby who presents with ‘a lump in the neck’ and ‘abnormal neurology’ certainly demands a careful history and examination.

Uncommon causes of torticollis

Congenital vertebral abnormalities:

The SCM is supplied by the accessory nerve (CN XI), which exits the skull through the jugular foramen. Anything affecting the structure of the upper cervical spine or skull base could compress the nerve root of CN XI and cause torticollis.

Congenital vertebral abnormalities often come along with other congenital abnormalities, as part of a syndrome (two examples are briefly described below, for interest). For this reason a child presenting with torticollis who is known to have other congenital abnormalities should be carefully examined with the possibility of an unusual syndrome kept in mind. [5]

MURCS syndrome (Müllerian duct/renal aplasia/cervicothoracic somite dysplasia) is a rare condition affecting 1 in 5000 female infants that has been associated with congenital torticollis in some cases due to aplasia of the posterior vertebral arch [6]

Klippel-Feil syndrome – cervical spine fusion is seen along with a host of other symptoms [7]

Posterior fossa tumours, tumours of the cervical spine, atlas and axis – these are very rare and should be part of the differential in older children who present with acquired torticollis. [8, 9] Posterior fossa tumours, when they present with torticollis, usually have accompanying symptoms of intracranial pathology (headache, nausea, vomiting, eye signs) [10]

‘Mimics’ of torticollis

‘Ocular torticollis’ occurs when there is 4th cranial nerve palsy. The superior oblique muscle, supplied by CN IV, causes the eye to look inwards and downwards. Paralysis of the muscle means the eye cannot adduct or internally rotate, and this causes torsional diplopia, which the child ‘corrects’ by tilting the head position. Adopting this position over a long period of time eventually causes contracture of the SCM. [11] This condition can be ruled out by using the cover test (watch a 7 minute long Youtube video with a rather disconcerting picture of a huge eye in the background here). When the affected eye is covered, the child should spontaneously correct their head position (in the early stages, before muscle contracture has occurred).

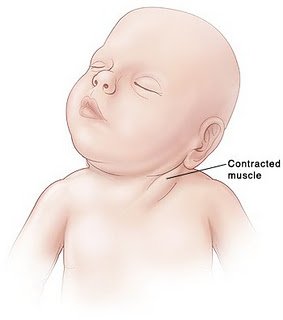

Examination

Appearance (see image): The head is tilted to one side (to the side of the affected muscle), and the chin is turned to the other side. There is stiffness, from the lack of movement, so there may be pain when the neck position is passively corrected.

A lump may be felt in the distal SCM.

Investigation

The key is to differentiate between muscular torticollis (ie common, benign, easily correctible) and non-muscular torticollis (ie possibly secondary to neurological, ocular or vertebral pathology, and needing further investigation.

If there is a lump palpable in the SCM, it needs to be differentiated from other causes of a lump in the neck. Ultrasound is the best first line investigation – it detects fibrosis of the muscle (diagnosing torticollis) but would also pick up abnormal lymph nodes or masses.

Fine needle aspiration would be the next step if there was any uncertainty of the diagnosis, but this is rarely needed.

Treatment

Once muscular torticollis is confirmed:

Physiotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. Even when there is severe fibrosis of the SCM, physio is effective in 98% [12]

- Neck stretches, performed regularly, moving the neck in the opposite direction to the affected muscle (tilt head sideways towards non-affected side, rotate towards affected side). Physio referral is indicated so parents can be taught the correct way to perform the stretches.

- Let the baby spend more time lying on its tummy, to strengthen neck muscles

- Use baby chair or Fraser chair to minimise the time the baby spends lying flat

- Encourage head turning to affected side by using toys, distraction, feeding from that side

- Physiotherapist may advise use of a neck brace in certain cases.

(The above advice adapted from ‘Physio Questions’ [13], a blog by an Australian physio – torticollis featured as a blog entry in August 2010)

Surgical treatment is very rarely needed – only in instances where conservative management has failed after 6 months of treatment. When surgery is performed, the operation is a bipolar release of the SCM, and this has been found to be highly successful, even in patients older than 5 years [14] and into adulthood [15]

Alternatives to surgery?

A recent successful non-surgical development in treating cases resistant to physio is using botox injection. [16] The evidence for chiropractic treatment is weak, isolated successful cases have been described, [17] but there has been no randomised controlled trial. There are also reports of infants with torticollis caused by neurogenic tumours being treated (unsuccessfully) by a chiropractor before the correct diagnosis was made, [18] so it is imperative that parents have consulted a doctor before they choose to seek chiropractic help.

References:

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3566514?tool=bestpractice.bmj.com

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21376202

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7484683

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18795328

- http://web.jbjs.org.uk/cgi/reprint/71-B/3/404

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21553338

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1264848-overview

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22095422

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20638308

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8784707

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/868283

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21843719

- http://physioquestions.blogspot.com/2010/08/are-you-worried-about-your-childs.html

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22045346

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19036153

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16470158

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8263436

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2484567/?tool=pmcentrez

October’s Paediatric Pearls

October’s edition is joint again this month on account of my right radius being fractured and its being too difficult to type and format text boxes with just my left hand… I am obviously not quite as good at ice-skating as I thought I was. All the topics this month should be of interest to both the ED and primary care teams anyway: a paper on paediatric early warning scores, the start of our neurodevelopment series, an update on services for bereaved children and their families and some useful links on the subject of head-lice.

Age of walking

It is not uncommon for us to be referred not-yet-ambulant children just past the 18 month “upper limit of normal” age of walking. The majority of these children are using means other than crawling to get around. I had vague recollections of having seen a table once detailing the 97th centile for walking in children who bottom shuffle, commando crawl or roll everywhere but I spent 2 or 3 fruitless hours searching the literature for it a couple of months ago. So I was ironically excited this month to find that Archives of Disease in Childhood had reproduced it! One of our current registrars, Dr Amy Rogers, has kindly put together an article for Paediatric Pearls with nuggets from that paper (Sharma A Developmental Examination: Birth to 5 Years. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2011;96:162-175 doi:10.1136/adc.2009.175901) which summarises normal development and when it would be prudent to refer children for further developmental assessment:

Approach to developmental assessment – birth to 1 year: Motor1

1) Elicit parental/carer concerns. Questions to ask:

- Do you have any concerns about the way your baby moves his arms/legs or body? Have you ever noticed any odd or unusual movements?

- Has your baby ever been too floppy or too stiff?

- Does your baby have a strong preference for one hand and ignore the other hand?

2) Gather information on social/biological risk factors:

Risk factors for poor developmental outcomes

| Biological | Family and social |

| Prenatal: drug/alcohol use, anti-epileptics, infection | Poverty, neglect, abuse, low maternal education, parental mental illness, inadequate parenting, disadvantaged neighborhood, absence of social support network |

| Perinatal: Prematurity, low birth weight | |

| Postnatal: Infection, severe hyperbilirubinaemia, injury, FTT, epilepsy |

3) Observe/elicit behavior and interpret findings

Note posture and movement. Examine tone. Elicit primary (Moro, grasp and asymmetrical tonic neck reflex) and support reflexes (downward, sideward and forward). Video clips of all these reflexes can be seen at http://library.med.utah.edu/pedineurologicexam/html/newborn_n.html.

What is not normal?

- Fisting of hands beyond 3 months

- Poor head control at 4 months

- Primitive reflexes beyond 6 months

- Flexor hypertonia in lower limbs beyond 9 months

- Not sitting unsupported with straight spine by 10 months

- Not walking by 18 months

BUT preterm infants often have delayed motor milestones, early hypotonia and longer lasting asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. Children with atypical pre-walking movement patterns (ie. non-crawlers) are late in achieving independent sitting and walking.

Pre-walking movement pattern and motor milestones (97th percentile)2

| Movement pattern | Sitting (months) | Crawling (months) | Walking (months) |

| Crawling | 12 | 13 | 18.5 |

| None – stand and walk | 11.5 | 14.5 | |

| Creeping/commando crawling | 13 | 15 | 30.5 |

| Rolling | 13 | 14.5 | 24.5 |

| Bottom Shuffling | 15 | 27 |

Refer if concerned as delayed motor development may be a marker for motor disorders and may have a negative impact on a child’s performance in the cognitive and social developmental domains. There is more information on delayed walking in a Patient Plus article written for health professionals available at http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Delay-In-Walking.htm.

1 Sharma A Developmental Examination Birth to 5 Years. ADC Educ Pract Ed 2011;96:162-175

2 Robson P. Prewalking locomotor movements and their use in predicting standing and walking. Child Care Health Dev 1984;10:317-30

Combined GP and ED versions for August 2011

Well the BMJ produces 2 journals in one in August so why can’t I? All the topics featured this month are relevant for both GPs and ED doctors – for once – so you have a joint newsletter. I have covered headache this month, Vitamin D (by popular request) and we have started the “Feeding” series requested by my ED senior colleagues. It seems appropriate to have covered breastfeeding first. Do leave comments below.

Migraine headache

I featured a headache guideline from Great Ormond Street Hospital in August 2011’s Paediatric Pearls. My colleague, Dr Simon Whitmarsh, has kindly allowed me to upload his migraine headache patient/parent information leaflet which I hope you and your patients will find useful. Please ensure that, as a courtesy, you acknowledge it as Simon’s work when you use it.